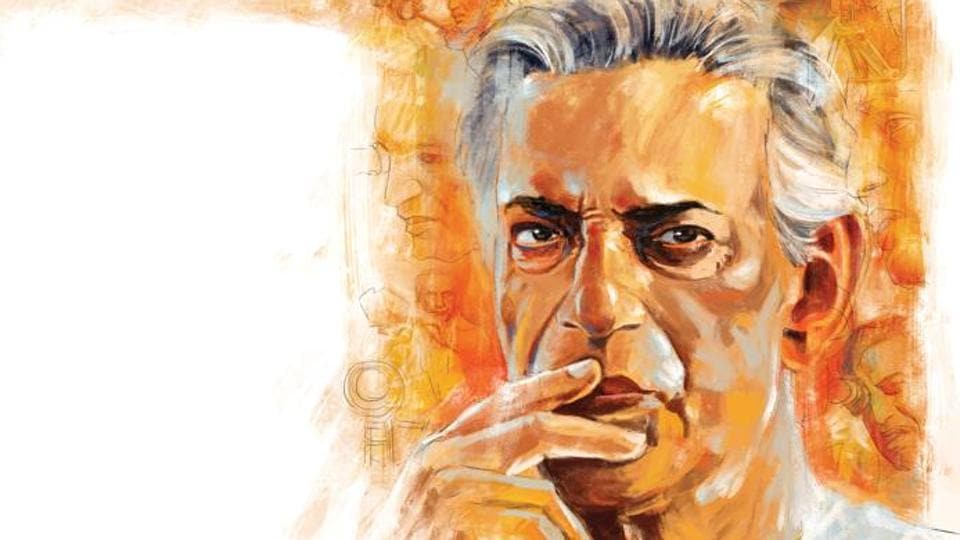

Given the focus on economic disparity-protestors’ complaints, backed up by the Calcutta Tram Workers’ Union, that the company was raising rates despite already robust profits-we can recognize this struggle as a “mass movement” against neocolonial economic and political influences, as well as for what is now known as a “right to the city,” in which residents assert themselves in shaping urban spaces and social relations (S. In 1953, for example, when the Calcutta Tramways Company (CTC)-still under British ownership-raised second-class fares, ensuing protests lasted for over a month, involving demands for governmental intervention, boycotts, general strikes, barricades against police, prison hunger strikes, and numerous efforts to negotiate with the government protestors endured tear gas, mass arrest, and police shootings (S. 2 But working classes in Calcutta had long staked a claim to this form of transportation historians single this city out for the vigor and sometimes violence with which residents would protest increases in tram fares, both during and after the colonial era (S. By 1963, many tram systems in India had closed or were on the verge of shutting down, viewed-as a recent newspaper report explains-as “a relic of the British era,” incompatible with the country’s “modernizing drive” and the “traffic snarls” emerging from increases in both urban populations and the numbers and types of vehicles on the road (Thomson and Sharma). In this way, Ray’s shot of this enigmatic object evokes the process of creating a “mental image” of a city, in Lynch’s terms: combining current perceptions and remembered experience in ways that render a space legible and shape inhabitants’ sense of their “relationship” with that space, which may, Lynch warns, be either “harmonious” or “fear”-inducing (2-5).īut even as the shot suggests a challenge endemic to urban life generally-and even as it eschews the physical structures of Kolkata, then rendered Calcutta in English- Mahanagar’s opening shot points to a history of conflicts specific to that city. Depicting a mechanism of mass transit, the shot points, at one level, to questions of visual and spatial perception that have been central to discourse concerning the modern city: how, Kevin Lynch asked in 1960, are residents-let alone visitors-to comprehend a space that is really an agglomeration of spaces, always changing in themselves and in their relationships to each other, and in which “at every instant, there is more than the eye can see, more than the ear can hear”? In Mahanagar, though we cannot see the tram car-let alone the street-the sometimes curving and sometimes intersecting cable suggests unseen neighborhoods, passages from one space to another, buildings and green spaces “waiting,” in Lynch’s words, “to be explored” (1). Aside from the pole and cable, viewers see only sky, occasional bits of architectural detail or trees rising above the street, and hazy images of intermittently passing birds.ĭirector Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar (1963)-translated to The Big City in English-begins with a rather puzzling image, pairing an electric tram car’s trolley pole with a cable, but not the car itself (fig. For the first two minutes of Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar (1963), the film’s titles overlay a shot of an electric tram car’s trolley pole moving along a cable extradiegetic music accompanies the sounds of its steady movement and the occasional friction of its passing through couplings and interchanges.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)